Dialogic Objects

Kimberley Foster and Bridget McKenzie led the activity Dialogic Objects.

In this, they invited participants to practise finding and mapping associations around their choices of objects from Bridget’s handling collection, part of Climate Museum UK’s resources. Then, having practised free and expanded interpretation of objects, they mapped their own meanings around artworks commissioned for this project by Kimberley. They were able to handle these objects, which combine and add to found objects. Reflection discussion drew out the participants’ responses in relation to environmental themes, in particular making visible what is often hidden in the impacts of consumer objects.

What Happened During the Sessions?

In each 45 minute session, Kimberley and Bridget introduced themselves and key concepts about using the objects they had collected and made. For example, Kimberley showed a headpiece made from wooden shoe lasts. This is an object made as part of her collaborative practice as sorhed and is used to talk about the potential of holding more than one meaning within one object. There is the possibility of knowing the original identity of something and then perceiving it differently when it is handled or performatively encountered. When these shoe lasts are placed on the head they become animal ears. This afforded more open thinking, vividly showing the importance of alternative interpretations of an object.

Then we modelled a desired process of mapping these potential and layered interpretations with an object from the museum collection - a shoe last - expanding out from observation of material clues to more personal and philosophical associations. This included our memories or immediate connections to the material encounter.

We explained that there is a personal connection to the shoe last for both of us, in that we both live in Norwich, a city where the manufacture of shoes has shifted from handcrafted to the invention of standardisation through to the closure of fifteen factories as shoe production has moved to Asia, part of the harmful fast fashion system.

Exploring the CMUK Handling Collection

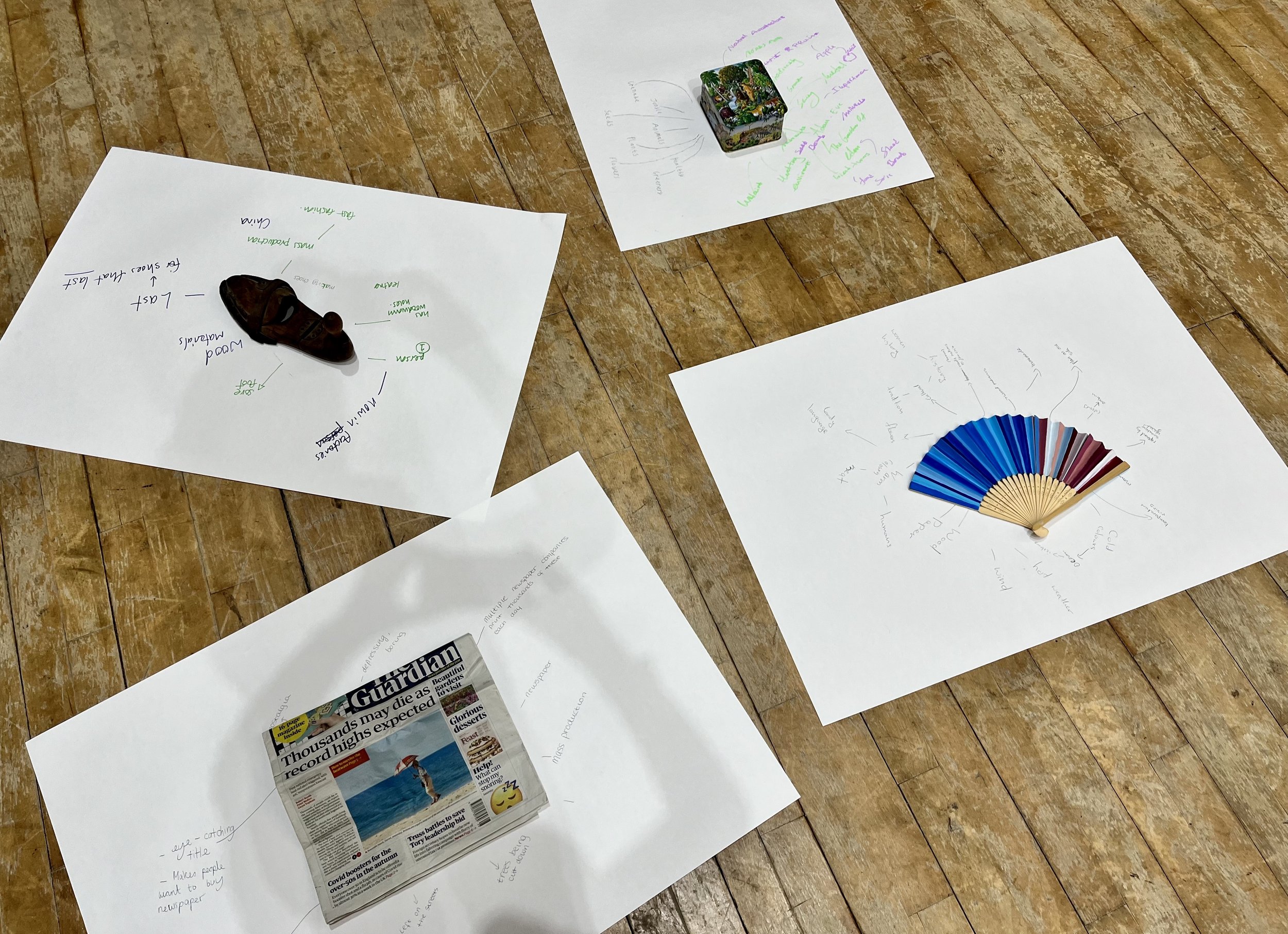

Working in groups of 3 or 4 around big sheets of paper, we invited participants to practise finding and mapping associations around their choices of objects from the CMUK handling collection, gathered by Bridget to illuminate aspects of the Earth crisis. These include, for example, a tea towel of beef cuts, a newspaper from the day of an extreme heatwave, an orangutan cuddly toy and a sweet tin printed with Adam & Eve in paradise.

Objects from the CMUK handling collection with comments and words written about them on paper.

Students discuss objects from the collection, including the orangutan.

Newspaper, fan, shoe last and box from the CMUK handling collection on the floor, surrounded by comments during a workshop.

A seed bomb in a decorated tin, part of the CMUK handling collection, surrounded by comments from workshop participants.

Participants choose objects from the CMUK handling collection.

Exploring Pedagogical Art Objects

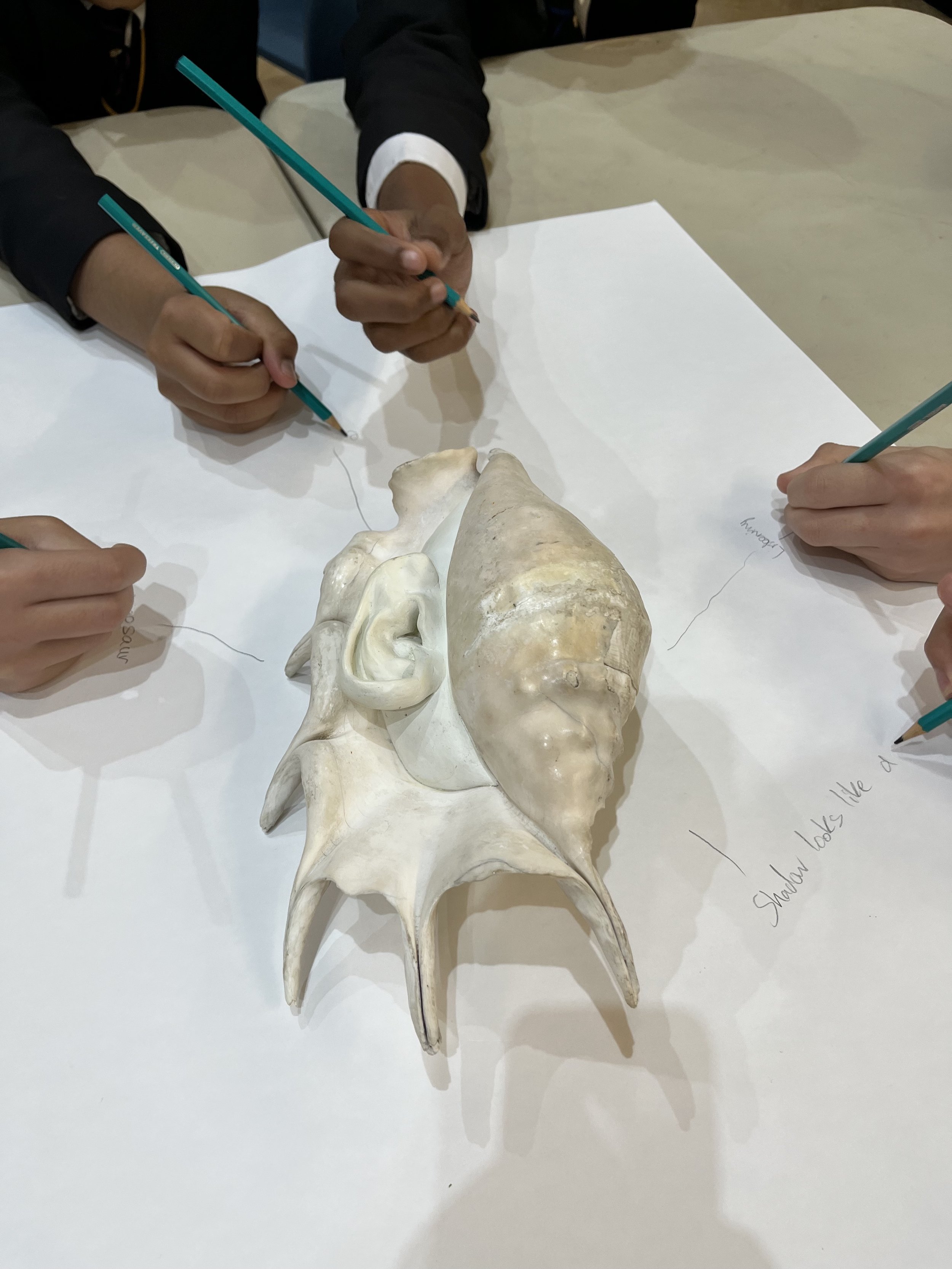

After this practice with functional objects, Kimberley introduced her own artworks, including a red megaphone stuffed with painted plastic model trees, a round buoy with human eyes in its rope-holes, a white conch shell filled with plaster moulded as a human ear, a drum lined with felt and embroidered with red coral or blood capillaries, and a wooden dustpan and brush affixed with colourful clay beads and fishing line to resemble a ghost net and floats.

As there were fewer objects than before, the participants were clustered into larger groups. After a short time, the artworks were swapped between groups so that everyone had a chance to explore at least two of them.

-

The object is a hand drum and looks normal until it is turned over. The underside of the drums skin is now felt and is embroidered with red. The stitches are thick and therefore stand slightly up from the surface of the felt, if you run your fingers across them, the channels of threads can be felt and traced across the surface. Made in relation to differing and overlapping imagery, the embroidery might suggest a skeleton tree, lung capillaries, roots, or coral like forms. Again, like the megaphone the drum implies sound although the bang of the surface is dampened by the internal felt buffer. The restrained drum beats in a different way.

The drum might feel less immediate or obvious than the megaphone object, the stitching slows down the thinking slightly and makes the person handling it feel more closely.

-

An object made prior to the project but used in the project workshops. This was made as part of collaborative partnership sorhed with Karl Foster.

-

The red shiny plastic megaphone is stuffed with plastic model trees, different varieties represented in this fake gathering. Trees were painted with differing colours that reflected autumnal shades and identified the trees between states of change. They look between the full bloom of summer and the shedding of their leaves. The object was made as a simple materialised gesture; offering a potential demonstration and allowing those holding the object to potentially think about how a shout for change could be heard. However, this is a noiseless act, if we hold the object to our mouths and try to speak through it our voice is no longer amplified. The removal of the buttons that usually would give volume to a voice is thwarted. The imagined sound coming from the megaphone is changed to a model forest. The trees become potential breath, the lungs pushing out the carbon dioxide, the trees stopping the breath and taking it in.

This object and the two incongruent parts it is made from come together in a simple form, held in the hands and moved by the body. The objects don’t convey one meaning but the chosen materials carry potential ideas that can be developed through the act of handling them.

Examples of comments

It reminds me of deforestation.

It’s like we are breathing out fumes into the forests.

We are turning the foliage brown.

It makes me think of a failing body – it’s gone wrong.

We can try and shout with it

We might demonstrate using it.

-

An object made prior to the project but used in the project workshops. This was made as part of collaborative partnership sorhed with Karl Foster.

-

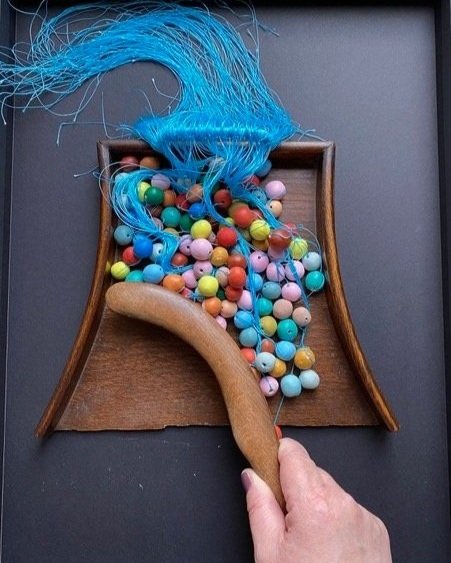

On the wooden dustpan and brush, there are a collection of handmade and individually painted clay beads. Each bead threads onto thin blue fishing line, and each is individually tied to the handle of the dustpan. As the threads fill the handle they knot and twist, unable to be untangled. The more the object is moved, the more the beads are knotted together becoming clump- like. Rather than staying as independent elements they become one woven mess. Even if the person handling the object tries to trace and free a bead from the knot it is impossible and the more you try to un-attach them, the more embedded they become. The more the object is used, the more that the painted beads start to chip and become damaged – removed from the perfect original form.

Ideas of nets emerge, or entangled fishing lines, captured fish perhaps, or knotted ideas, could they be swimming buoys no longer able to float. The brush that is part of the object can push and try and tidy up the beaded mess – pushing into a corner of the object. However, this it is unsatisfactory, and the beads take too much space, knock and pile into each other. We can’t simply tidy this mess or untangle the knots.

-

An object made prior to the project but used in the project workshops. This was made as part of collaborative partnership sorhed with Karl Foster.

Our intentions were to draw out conversations to grow confidence to speak about provisional and complicated ideas, while also triggering interests in the impact of industrial production on the climate and ecosystems. Our activity, of the three in this project, was the most focused on materials and consumerism. The objects offered potential for rich dialogues about the excesses of mass production and waste.

Kimberley’s objects, in particular, stirred uncanny feelings of empathy leading participants to ask questions such as: ‘If trees could speak what would they say?” and “Are shells living things that can hear?” and “The ocean wants us to listen to it”. The artefacts were stimuli for shifting perspective, so that things all around us become animated and extraordinary, with ecological connections made visible when they are so typically ignored. We asked that the groups paid closer attention to the material and their meaning through this exercise.

Throughout, we wanted to trigger personal and divergent responses, different for each individual and emerging from sharing their different ideas. The initial mapping of ordinary objects enabled them to look again, to see how each mundane thing can have meaning and impact on our environment. We hoped this would build confidence and a technique to extend ideas and connections from the artist-made objects. As they explored different functional, aesthetic and symbolic objects, we as facilitators and teachers injected small amounts of factual content that resonated with their ideas and questions.

Students write their thoughts about the shell with ear object on paper surrounding it.

All of the art objects laid on paper alongside each other on the floor, with participants sitting and looking at them all as a group.

Girl holds red megaphone art object at one of the workshops.

Two students write down their responses to the dustpan object.

Two students looking at the drum object and writing down their responses on paper during a workshop.

Reflections

Two dominant ways of interpreting objects emerged: 1) Objects are ‘freighted’ with meanings like a sponge that can be squeezed, or a ship whose cargo can be unpacked. 2) Objects are triggers for meanings that can be generated between people in conversation, in relation to situations, and not held within the object in such a denotative way. We discussed between us the idea of an object having a shadow, more than is normatively known, but still visible.

We noted that ordinary objects can be as open to connotation as artist-made objects, but that encouragement is needed to be open-ended and imaginative in reading them. On the other hand, the artist-made objects could be used to stimulate discussion about environmental ideas, but support with nuggets of information was needed to extend their conversations.

We did aim to integrate messages into our workshop that encouraged the young participants to have a voice, to raise their environmental concerns with others and influential people. However, it was only in the iterations at the end of the project that we were best able to do this, as environmental issues became a more overt part of the introduction.

A practical challenge was the short amount of time to explore complex meanings, and a more satisfying workshop would have included a making activity, although we provided resources for teachers and students to follow up in their own time and space.

Conclusions

In general, the two intended outcomes of the project for young people were to broaden their understanding of Earth crisis issues and eco-social solutions; and to give them experience of creative methods to express their ideas, so that they can develop confidence to engage peers and influencers. With these two outcomes, we had to overcome a duality in our activity designs, between educating about these issues and enabling exploration through creativity.

By working in groups, participants could pool their environmental knowledge to enrich the interpretations of objects, and progress more quickly to metaphorical and emotional ideas. When there was a wider range of knowledge in the group, they needed fewer prompts and could generate imaginative ideas with a greater sense of intrinsic motivation. On the other hand, there could be a risk that participants (or accompanying teachers) who come with more knowledge drive the discussion for too long into denotative territory, or that someone would introduce a disturbing piece of information about the crisis that would limit the imagination. The introduction of Kimberley’s artworks reduced the risk of a denotative turn, and immediately created an ethos of possibility.

With more time for exploration and making inspired by her artworks, we would be able to create a rich space for the participants to voice their questions and experiences in nuanced ways around the impacts, causes and solutions of the crisis, exploring cultural biases, narratives and conundrums.

Kimberley discussing some of the objects from Climate Museum UK with student participants

A student holds the red megaphone during a workshop

Bridget stands near with students at a table, discussing the red megaphone

Inspired?

Access our free resource library to help run your own workshop.

Please recognise our project when using our work, and get in touch if you are interested in finding out more about our methods and findings.